dial entirely and show a suggested exposure with light-emitting diode (LED)

or liquid crystal displays like those found on digital watches.

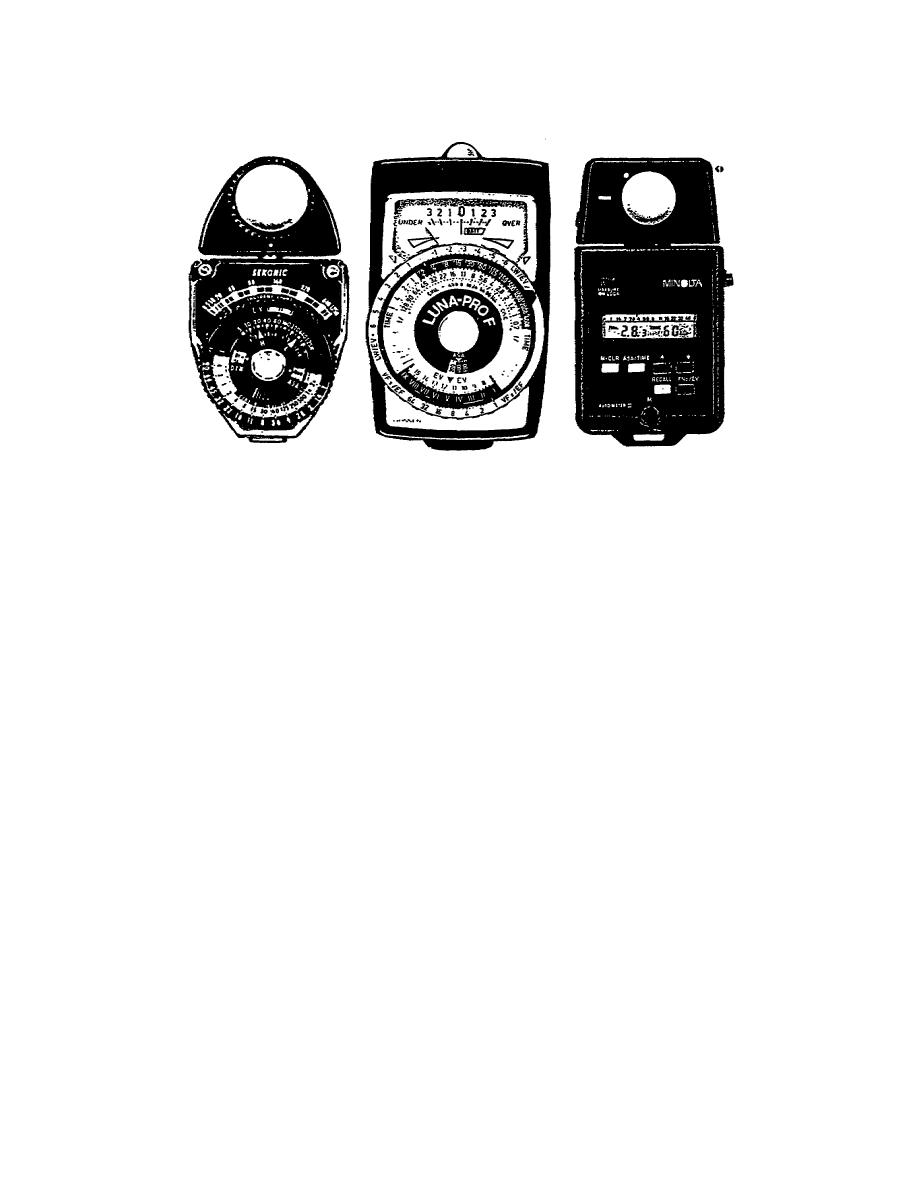

Figure 1-12.

Three types of light meters

5.

Take a look at the calculator dial shown in Figure 1-13. Once again,

this is something that looks complicated, but really isn't. First of all,

there's a little window, marked "ASA". ASA is just an obsolete abbreviation

for what we now call the International Standards Organization (ISO), and it

is, naturally, the same film speed we talked about earlier in this chapter.

Notice that only some of the film speeds are actually numbered. Others are

simply indicated by tick marks (fig 1-13).

This is what a complete film

speed scale looks like, and what those little tick marks represent.

By

turning the innermost dial, you can set any ISO number you wish, and this

adjusts the rest of the dial scales to match.

This is the most precise

scale available on the meter; each tick mark represents a 1/3-stop change in

the meter settings.

All the other scale markings are 1/2-stop or more

apart.

The outermost scale is a reproduction of the scale behind the

indicator needle, and next to it is an indent mark, in this case, a large

arrow.

This arrow is set to the same number the meter's needle moved to

when the reading was taken. The most important scale should look familiar

to you by now.

Remember the section on equivalent exposures and how to

construct an equivalent exposure calculator?

Well, that's all this is.

When you set the index mark to the number the meter needle fell on when the

reading was taken, you slid the f/stop scale along the shutter speed scale

as you did this. So now you simply choose one of the equivalent exposure

settings which match the dial and shoot your picture.

6.

You probably suspect that this isn't the whole story. First of all,

you need to know how to use the meter to take a light reading in the first

place, and second, you need to know how to interpret what the reading really

means. Let's talk about taking readings first.

17

Previous Page

Previous Page