shape your negative or paper is, there is no law that says you must force

your photo to fit what you have.

You may make a long, thin picture or a

square picture, or anything in between, if the scene calls for it.

Admittedly, the shapes you are given by the manufacturers are the most

popular, but they aren't engraved in stone. Paper is easily cut. One of

the easiest ways to control format is to turn the camera from horizontal to

vertical. This is a simple but distressingly underused advantage of cameras

that take rectangular pictures. If your subject is taller than it is wide,

it probably would be better suited to a vertical format.

But many

photographers stubbornly hold the camera horizontally and back away until

the long subject will fit into the short side of the picture frame. It is

so much easier to just turn the camera on its side and fire away.

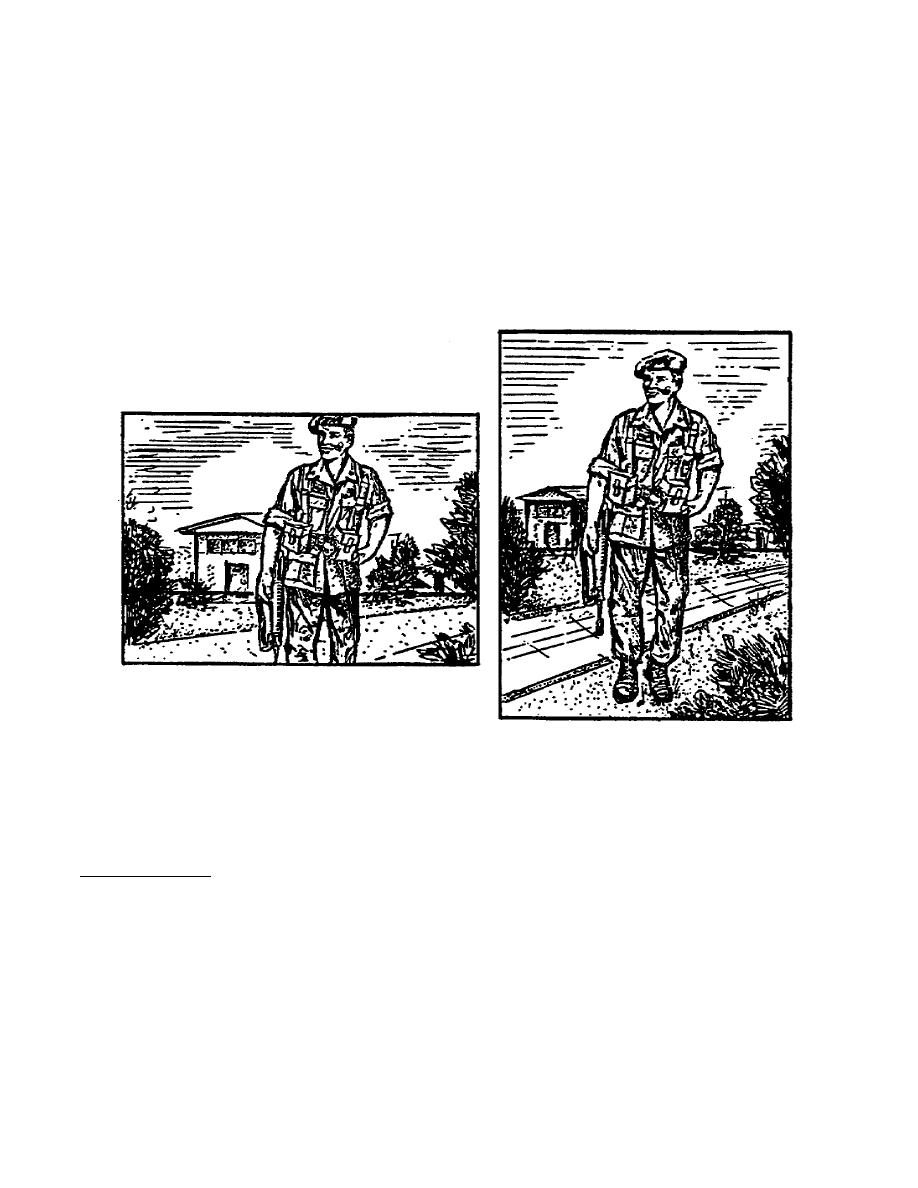

Figure 3-6.

Choose a format which fits your subject

f. Lines. Lines are one of the strongest compositional tools available

to the photographer (or for that matter, any visual artist).

(1) Few things serve better than lines to direct the viewer's

attention to a specific spot in a scene.

Lines that do this are called

leading lines, and they can be explicit or implied. Explicit leading lines

are those you can actually trace out with your finger in the picture. Fence

lines, pathways, roads, and railroad tracks, are all examples of explicit

leading lines. The most common example of an implied line is the direction

of a person's gaze. If a person in a photograph is seen to be looking at

something else also in the picture, the viewer's eyes are almost compelled

to look at the object too. No actual line can be seen, but the idea of a

direction of gaze is extremely powerful.

This becomes a problem if lines

become contradictory. If two or more people are shown in a photo and they

are each looking at something different, then the viewer's attention is torn

between the different subjects, usually to bad effect.

58

Previous Page

Previous Page