c. Very few editors can work accurately without moving the tape reels by hand. Practice doing

this until a word recorded on the tape at normal speed can be recognized. Learn to recognize sounds

when the tape is moved at less than normal speeds. The ability to distinguish one sound from another at

low tape speed will come in time, but only after much practice.

4.

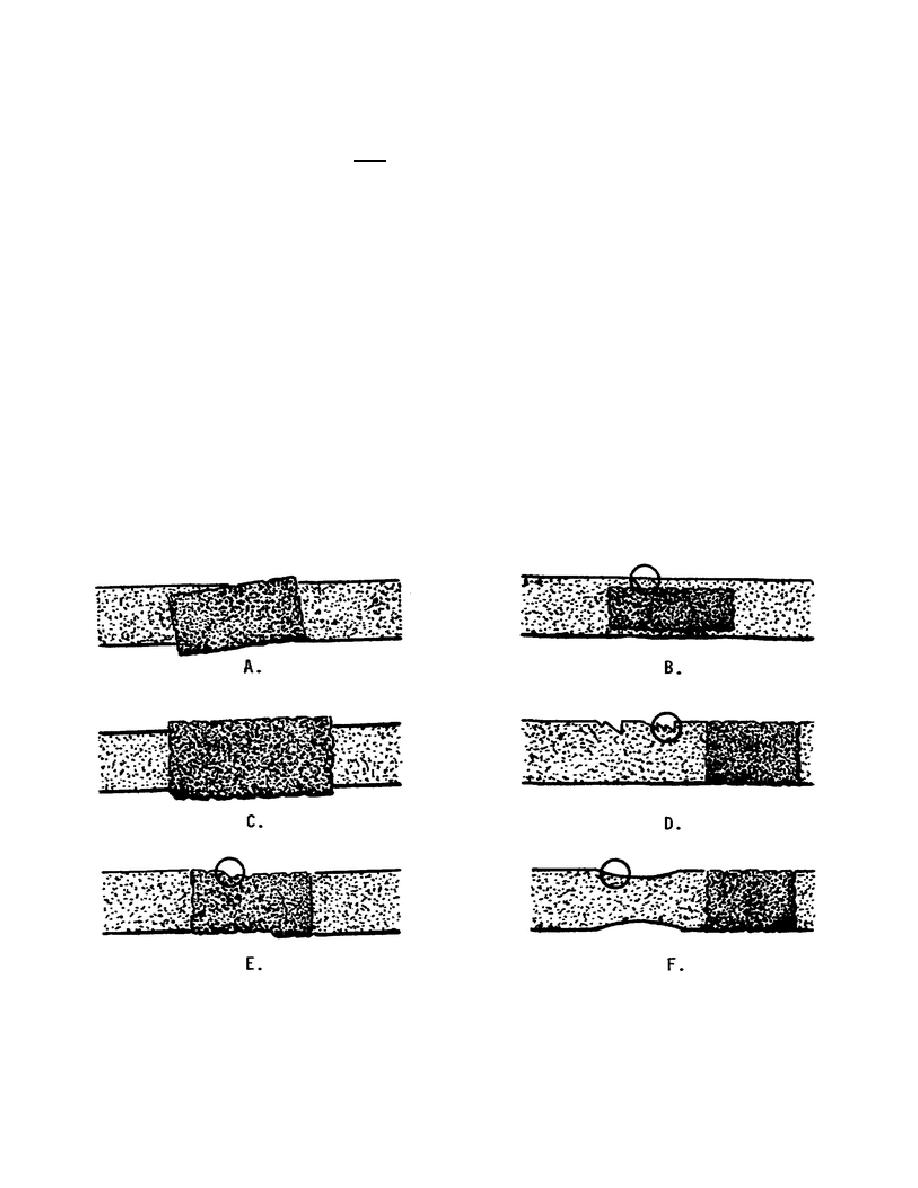

Improper edits. The angle at which the recording tape is cut is not critical as far as strength is

concerned as long as the tape is cut on a diagonal and both ends are cut at the same angle. Tape cut with

a square end invariably makes a noisy splice. It also takes more of a beating as it passes overheads and

idlers, and so it is more likely to fail. Devices with an adjustable cutting angle gives no advantage and

may mismatch the tape ends.

a. Splicing devices. As long as the tape ends are cut properly and barely touch, most splicing

devices will keep the tape from slipping to one side or falling at an angle. Some really cheap splicers

that use a pressure-formed tape channel take on an angle where the tape cutting slot is sliced through the

channel. If the joined tape ends are not absolutely flush, an accumulation of oxide flakes and other

foreign matter in the gap will make a noisy, weak splice. In editing blocks particularly, carelessness in

positioning tape ends can easily produce an overlay ready to snag on just about anything.

b. Ragged edges. In extreme cases, poor splicer design can even damage the tape. Ragged

edges in the channel of very cheap blocks can snag and nick the tape. With thin polyester-base tapes,

too, there is the danger that a device with too good a grip--plus a careless user--can yank the tape until it

stretches or its edges curl (fig 4-36).

Figure 4-36. Examples of how NOT to splice tape

64

Previous Page

Previous Page